India's vaccine drive: Stories from the best and worst districts

Vaccination against Covid was always going to be a massive challenge for India - a country of some 1.4 billion people.

The programme had a smooth enough start. India began giving jabs on 16 January, first to frontline workers and those above the age of 60. But by May, when the drive was thrown open to everyone above the age of 18, the country was severely low on stocks - even as demand surged in the wake of a devastating second wave.

The supply shortage, however, has not been the only challenge. India's effort to vaccinate its people has had varying success across regions because of other issues, from planning to infrastructure to misinformation.

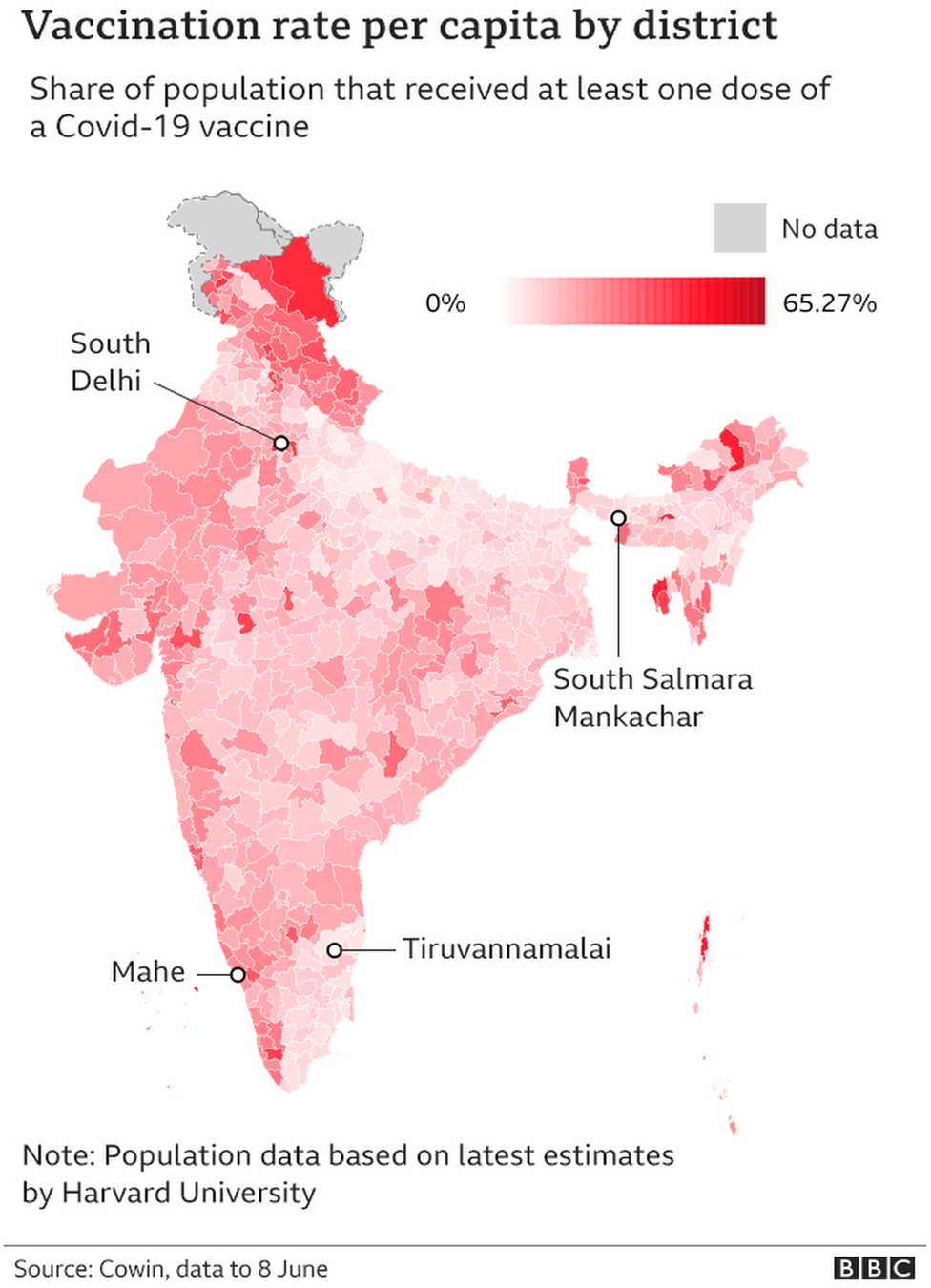

Analysis by the BBC of 729 districts for which data was available shows wide disparities in per capita vaccination rates - some districts have given jabs to half their population, while others have vaccinated as little as 3%. Some urban and sparsely populated districts have fared better than other large or rural ones.

Here's a snapshot of what went right - and wrong - in four districts.

Two of them - Mahe and South Delhi - are near the top of the table, while the other two - South Salmara Mankachar and Tiruvannamalai - have struggled to vaccinate a sizeable number of their people.

Planning is key

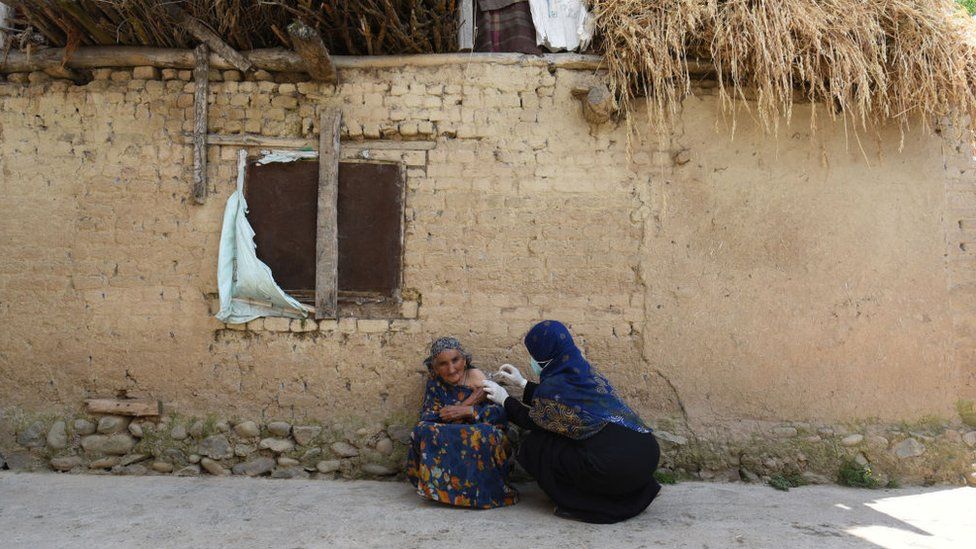

When Shivraj Meena took charge of Mahe, a tiny district on India's south-western coast, in February this year, he had his work cut out.

The district's population - about 31,000 people - had to be vaccinated quickly because the second wave appeared to be looming already. But Mr Meena found that people felt unsure about the safety of the vaccines, and were also reluctant to come to the vaccination centres, fearing crowding.

At just nine sq km (3.5 sq miles), India's smallest district has limited health infrastructure. So Mr Meena drew up a plan.

"I called political leaders, religious leaders and community elders for meetings where I explained the efficacy of vaccines and pointed out that frontline workers had seen negligible adverse reactions after taking their shots," he said.

He then created 30 teams - made up of health workers, nurses and teachers - which went door to door, counselling and enrolling people, and issuing appointment tokens for vaccination.

The strategy worked. More than 53% of Mahe's population has been given the first dose so far, making it the top-performing district in the vaccine drive.

"You just need to identify the problem and the solution can be found accordingly," Mr Meena said.

'We are scared and suspicious'

South Salmara Mankachar, a remote district in India's north-eastern state of Assam, is the worst performer so far.

In these agrarian, largely Muslim villages bordering Bangladesh, officials have been able to vaccinate only 3% of the half a million people living here.

"I have heard that people die after getting vaccinated," said Monowar Islam Mondal, a farmer who has not got his shot yet. He alleges a conspiracy against the Muslim community.

Recent state elections saw the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) win after a divisive campaign that targeted unauthorised migrants from across the border, many of them Muslim.

Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma's claim that the BJP doesn't need Muslim votes was widely quoted in the media.

"The BJP does not like the Muslim minority and says that it will drive us out of Assam. Then why are they being generous and giving us free vaccines now? We are scared and suspicious, so we do not want these vaccines," Mr Mondal said.

It's a sentiment echoed by many others in the district. But officials said it was not the reason for low vaccine rates.

Deputy Commissioner Hiwre Nisarg Gautam said the low turnout is a result of the district's topography - people are unwilling to make the long trek from their homes to the vaccine centres.

Misinformation has derailed the drive

Another state that recently held an election and has shown poor levels of vaccination is Tamil Nadu, in the south.

Most districts here have given the jab to just 4-6% of their populations.

Tiruvannamalai, one of the largest districts, is also among the poorest.

"There was a lack of focus on coronavirus and vaccination during the election," said Saravanan, who maintains and repairs television cables.

His job takes him inside people's homes, but he hasn't been vaccinated yet. He said he never felt the urgency to take the shot.

"They speak about it now but they were silent then, as if corona was not there during the election."

Others cite fear of vaccines - a popular actor had died within days of taking his jab.

"There was a vaccination camp in the village. But people are afraid as actor Vivek died soon after taking his vaccine. I will take the vaccine, anyway. But as I am not moving around anywhere and staying at home, I thought I can take it later," said a farmer.

Dr Ajitha, deputy director of health services in the district, pointed to its huge size and population to explain the low rate of vaccination.

"We were struggling with a low footfall even before elections and vaccine hesitancy amongst the largely rural population has been a huge challenge."

The infrastructure trap

It's the opposite scenario in the country's capital - especially in South Delhi, one of the richest and the least populated of the city's 11 districts.

And it has fared the best. It has given the first jab to 43% of its 1.1 million residents.

The shortfall in supply had even many urban Indians complaining that booking a slot online for a jab was akin to playing "fastest finger first" - but 27-year-old Mahima Gulati, who lives in South Delhi, was among the lucky ones.

"It just took a few minutes - I booked for myself, my brother and a few friends and we got our jab at a government school just five minutes from my home," she said.

"There were no crowds, it was all very organised and systematic."

One reason is because South Delhi has more vaccination centres than other, more populous districts. And the more vaccines you give, the more you get from the federal government - at least that was the case before 1 May, when states were not buying shots independently.

"We are lucky to have big private and government hospitals that could set up multiple sites quickly and a more literate population that was motivated enough to seek vaccines as soon as they rolled out," district magistrate Dr Ankita Chakravarty said.

South Delhi's biggest advantage, she added, was its health infrastructure, which in turn, supported its vaccine infrastructure.

"And that's not something you can build in a day. It's a lesson the pandemic is teaching all of us."

Additional reporting: Dasappan Balasubramaniyan from Tiruvannamalai and Dilip Sharma from South Salmara Mankachar